In Bruges in Brogues

People in Bruges wearing more sensible shoes than me.

“Bruges is like an egg,” says Benedict. “The outer part, where the walls once were, is the egg white and the smaller city centre is the egg yolk. Although it is not very yellow.”

Benedict is taking me on a private tour of the West Flanders capital, where he was born sixty-odd years ago. “The egg is only seven kilometres so you can walk around it very easily. We’re going to walk in the footsteps of the Counts of Flanders and the Dukes of Burgundy and more.” I’m wearing brogues and my feet are killing me. I met Benedict last night at a restaurant. Our tables were quite close together and he overheard me talking about movies set in Belgium; three minutes later he offered to show me around town.

“Although the walls themselves are lost today, they are still in a sense visible in the form of the four surviving gates, the ramparts and one of the water towers,” Benedict continues. “The classic medieval street pattern wherein main roads lead to public squares, has largely been maintained. Can you guess what the other main source of mercantile traffic was?” I am about to say ‘canals’ when Benedict says, “Canals.”

We begin in Burg Square, home to the Gothic Stadhuis (city hall), dating from 1376. Like so many buildings in Bruges, it is well-preserved and spectacular. “Little wonder then that our city attracts around eight million visitors each year,” Benedict says, with the briefest blush of pride. Looking around it’s hard not to think that at least half of them are here today, a sunny weekday in late summer.

The Stadhuis.

Adjacent to the Stadhuis is the 12th century Basilica of the Holy Blood, best known as the repository of a glass phial containing a piece of cloth infused with the blood of Jesus. The story of how Christ’s blood ended up in a Byzantine perfume bottle in Flanders is complicated and probably false (as is the ‘blood’ itself), nevertheless I join the lengthy queue in order to take a five-second look at the ornate glass and gold tube (allegedly) containing Jesus’s juice. It is not a transcendental experience. But it is only €2.50.

Benedict (wearing soft, comfortable walking shoes) and I (wearing hard, chafing leather) continue through Huidenvettersplein, a small square that is the former location of a tannery. Along with every other square inch of the yolk of Bruges, it is almost absurdly picturesque. Above the lead-lined windows on the second floor of what is now a hotel-restaurant are reliefs displaying the tanning process; boiling the hides, beating the hides, turning the hides into uncomfortable leather shoes. “They used horse urine as a softener,” Benedict delights in telling me. “You can probably imagine the smell around here a few hundred years ago.”

Yes, I probably can.

Even the public seating is quietly superb. Writhing, green-painted wrought-iron dragons rise from the ground, their outstretched wings supporting time- and butt-worn oak planking.

We continue along a wide, linden tree-lined boulevard called De Dijver, parallel to a canal, and soon arrive at Beautiful Spot No. 276: the Arentshof, a small oasis of stone pillars and green trees in full bloom, ringed by stunning buildings from the 17th and 18th centuries. Nearby, the small, stone Bonifacius bridge is an exceedingly popular photo spot for tourists. Benedict derides for its lack of oldness. “It’s only from 1917 or so,” he sneers. My aching feet do not enjoy crossing the sharply arched bridge.

I can’t help thinking about what it must have been like negotiating these bumpy, skinny, crowded streets back when everybody wore clogs or crakows, those long, curly-toed shoes favoured by Counts and Dukes.

Over the bridge and around the corner is what Benedict calls “one of the blood spots in the egg” – Sint Jan Hospital. “It began taking patients in 1170; when do you think they stopped seeing patients?” I begin some quick mental calcu- “In 1977,” he answers himself. He goes on to explain that in the early days (before 1977) they somehow employed chicken anuses in an attempt to drain the boils of plague patients. It’s becoming clear that for Benedict, there is no such thing as too much information.

My feet are throbbing as we reach the large, popular, crowded Markt square, location of the spectacular of spectaculars – the Belfry, star of the 2008 film ‘In Bruges’. Benedict ignores it and points to the Craenenburg, a beautifully gabled 15th-century building where Emperor Maximilian I of Rome was imprisoned by the burghers of Bruges in 1488. After being forced to watch the beheading of one of his henchmen Max was released. Immediately afterward he punished the people of the city. “So what was the punishment he handed down?” Benedict asks. I wait half a second. “The punishment was that he banished all visitors to Bruges. And so by the end of the 16th century, the city’s power and wealth began to decline, and by the middle of the 1800s we were the poorest city in Europe – too poor even to demolish our buildings, which turned out to be lucky for us. Because slowly people began to discover our medieval heritage and, thanks to people like you, Sean, we have become an international tourist destination, making Bruges a wealthy city once more.”

I nod in appreciation of his finely-crafted (and possibly apocryphal) conclusion, but the truth is my feet are now so bruised, bloodied, blistered and broken that all I can think about it sliding them into the lush and welcoming slippers back at my hotel, which is mercifully just a few minutes’ hobble away.

The Hotel Heritage

I am in Bruges for a long weekend with my wife and daughter. We’re staying at the Hotel Heritage – a former private residence from 1869 that manages to be opulent and glamorous yet down-to-earth cosy at the same time. The abundance of still lifes, chandeliers and comfortable lounging areas and bars make me want to live here forever, as does the superb Belgian modern cuisine at Le Mystique, the hotel restaurant.

The morning after my tour of the yolk, following a delicious hotel breakfast in the spectacular dining room, I head around the corner to the Frietmuseum with my eight-year-old daughter, Sylvie. It bills itself as “the first and only museum dedicated to potato fries”. Because there’s only so much material one can deliver about the chopping and subsequent deep-frying of potatoes (and then dipping them in mayonnaise, as the Northern Europeans are wont to do), the museum goes into great – perhaps unnecessary – detail about the history of the potato itself; its origins in Peru; its molecular structure; its importation to Spain; the various diseases and insects that threaten it; and the many, many, many different tools used to unearth them. “This is way much more about potatoes than I want to know, Dad,” Sylvie says. And we’re only on the first of three floors.

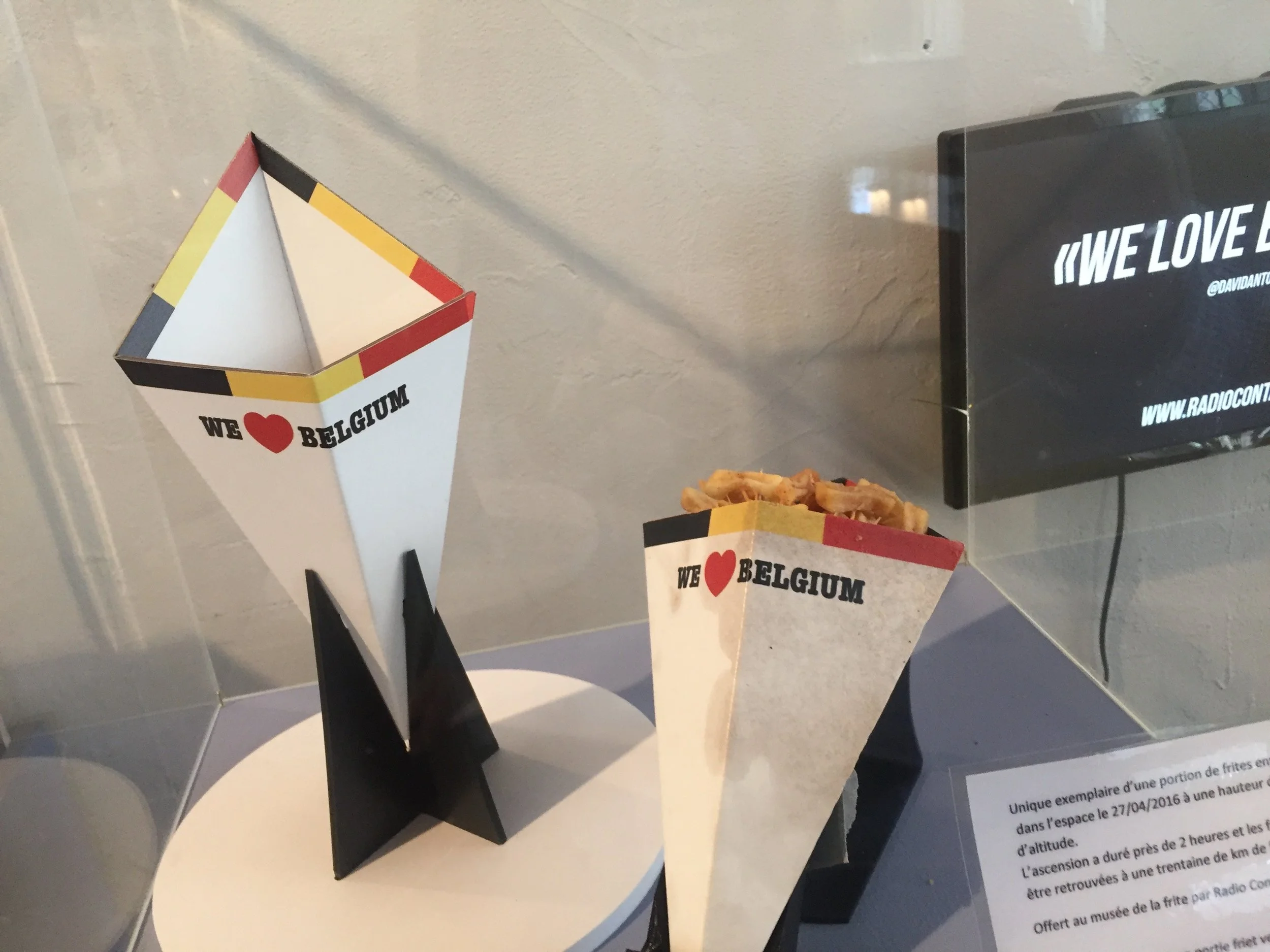

The second floor is where the real friets-y action happens: peelers, choppers and deep-fryers from across the decades abound. There’s also a recreation of a frietskot (friet-wagon) where you can pretend to run your own operation. There are recipes for several sauces, displays covering the history of the tiny fork used for skewering friets, and the paper cornet used for holding them. Nearby is a vitrine containing a replica of the cornet of friets that was, perhaps unnecessarily, sent into space (upper left). Sylvie observes that it is one year ago to the very day that this momentous event occurred.

The most alluring thing about the museum is its smell; salty, fatty, starchy and completely delicious. It emanates from the lower ground floor where there is a subterranean fry shop, offering friets and a choice of 21 different sauces, from simple mayonnaise to a sort of Belgian stew called stofvlees. Beneath the low, vaulted brick ceilings are a few coloured plastic tables and chairs, giving this oppressive old space a cheap, gaudy atmosphere. The friets take a while to arrive so anticipation is high. When they do finally reach us they are, almost inevitably, underwhelming – runty and bland, in desperate need of salt. They are overcooked and taste like they have been fried in historical oil.

“What other museums do they have in Bruges?” Sylvie asks, wiping mayonnaise from her lip.

“Chocolate and beer,” I tell her. “How about-“

“Chocolate,” she says.

It’s on the other side of the egg but I’m wearing sensible shoes today. “Sure,” I say. “Let’s go.”

Originally published in The Australian newspaper.

March 31, 2018